Recently, Google’s AI platform Gemini provided what was perceived as a “biased” answer to a question on the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, asking “Is Modi a fascist?”. Gemini’s response was that Prime Minister Modi was “accused of implementing policies some experts have characterised as fascist.” This answer drew sharp criticism from the Indian government, with the Minister of State for Electronics and Information Technology (“IT Minister”) accusing Google of violating India’s IT laws and posting on X that unreliability of AI platforms could not be used as an excuse for them to be considered exempt from Indian laws.

The IT Ministry’s Advisory

Shortly after, the Indian IT Ministry released an advisory (“Advisory 1”) on March 1, 2024 aimed at intermediaries and platforms on the use and deployment of artificial intelligence (“AI”). Intermediaries under India law are entities who can receive, store or transmit an electronic record or provide any service in relation to it, on behalf of another. This caused quite a stir amongst tech companies in India.

Advisory 1 (accessible here) requires intermediaries and platforms to ensure that their AI software or algorithms do not permit users to either host, display, modify, publish, transmit, store, update or share any “unlawful content”.

The unlawful content in question is detailed under Rule 3(1)(b) of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 (“2021 Rules”). It includes, inter alia, content that

- belongs to another,

- is obscene, pornographic, or invasive of another’s bodily privacy,

- is harmful to children,

- infringes IP rights or,

- is in the nature of an online game but is not verified as an online game, including any advertisements in this regard.

Further, the intermediaries and platforms are required to inform users about the consequences of dealing with such unlawful content. According to Advisory 1, some of the possible consequences include disabling access to or removing the non-compliant information, suspension or termination of access or usage rights of the user to their account, in addition to the punishments subsisting under Indian laws. Advisory 1 instructs intermediaries and platforms to provide such information through their respective terms of service and through user agreements.

Advisory 1 also warns against the use of AI to spread misinformation or deepfakes. Intermediaries using software or resources that facilitate the creation of this type of content are required to label or embed it with a permanent unique metadata or identifier which can be used to identify the users or computers posting the information, its creator and the tools used to create it, as a measure seeking transparency.

The most contentious part of Advisory 1 however, requires that any “under-testing” or “unreliable” AI models, large language models, or generative AI software or algorithms can only be made available in India after obtaining “explicit permission” from the Indian government. Further, the AI products can only be deployed after intermediaries and platforms appropriately label the possible and inherent unreliability of the output generated. This can be done through consent pop-up mechanisms.

Lastly, Advisory 1 warns that failure to comply with the provisions of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (“IT Act”) (i.e. India’s primary legislation on IT) and/or the 2021 Rules would result in potential penal consequences under the IT Act as well as criminal laws for the intermediaries or platforms or its users.

The intermediaries were given 15 days to comply with Advisory 1.

The Uproar and resulting Government Response

Predictably, Advisory 1 garnered significant amount of criticism from the IT sector, especially from startups, questioning its legality; believing it to be a rushed foray into regulating AI and a case of regulatory overreach, exacerbated by the advisory’s ambiguous phrasing and expansive scope. Some critics argued that Advisory 1 attempted to kill any kind of innovation and entrepreneurship within the startup ecosystem while others viewed it as an attempt to tighten government control given the impending general elections.

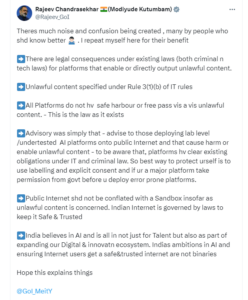

In response, the IT Minister, in a series of posts on X, clarified that Advisory 1 only applied to “significant platforms” and would not apply to startups.

The post further clarified that the advisory was limited to “untested” AI platforms.

Did Advisory 1 create more questions than answers?

Both Advisory 1 and the government’s clarifications have caused confusion about its scope and effect. While the IT Minister’s clarifications attempt to limit Advisory 1’s reach to “significant platforms”, this limitation does not appear anywhere in the official text, but only in the Minister’s social media posts, which are not legal instruments. Moreover, the terms “platform” or “significant platform” are not defined in Advisory 1, nor under the IT Act and the 2021 Rules. This is particularly pertinent as Advisory 1 is purported to have been issued to rectify the non-compliance of both these laws (especially the latter).

A logical assumption can be made that the reference to “significant platform” actually means “significant social media intermediary” as defined under the 2021 Rules, which seems likely to be the case given that Advisory 1 was issued to eight significant social media intermediaries, namely, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Google/YouTube (for Gemini), Twitter, Snap, Microsoft/LinkedIn (for OpenAI) and ShareChat. A social media intermediary is an intermediary which primarily or solely enables online interaction between two or more users and allows them to create, upload, share, disseminate, modify or access information using its services. Significant social media intermediaries are a class of social media intermediaries having more than 50 lac (5 million) registered users in India. However, Advisory 1 does not specifically make this clear.

Further, Advisory 1 uses terms such as “undertesting” and “unreliable” in reference to AI, which lack precise definition under the law. This absence of clear guidelines renders compliance with Advisory 1 near untenable, as subjective interpretations are inevitable without strict criteria explaining what constitutes undertesting or unreliable.

The revised Advisory

In response to the backlash received by Advisory 1, the government issued a new advisory (“Advisory 2”) on March 15, 2024 (accessible here), which superseded Advisory 1 and removed the requirement to obtain government approval before deploying AI models. Advisory 2 provides that undertested and unreliable AI models can be deployed in India only after appropriately labelling the possible inherent fallibility or unreliability of the output generated. The “consent popup” requirement has also been retained, with Advisory 2 stating that such mechanisms should be used to inform the users of the output being false or unreliable. The other parts of Advisory 2 while similar in intent to the Advisory 1, have a few differences, namely, the metadata should now be configured to also enable identification of any user or computer resource which makes changes to the original information and the consequences of non-compliance now applies to intermediaries, platforms, and users. Lastly, unlike Advisory 1, Advisory 2 does not provide intermediaries with a fixed deadline to comply with its requirements, instead requiring compliance “with immediate effect”.

How much legal Force do these Advisories really have?

Advisories generally do not have a binding effect. Their role often is to provide additional clarification to the masses on existing laws or regulations. Advisory 1 in particular, did not seem to reference any specific laws or regulations from which it may be drawing its enabling power to mandate seeking prior approval from the government.

The glaring question which therefore arises pertains to the legal basis behind the government’s actions to regulate AI, i.e. which law(s) empowers the government to issue guidelines to AI companies, given that the existing tech laws in India, especially the IT Act in its current state, do not seem equipped to directly regulate large language models. The legality of the 2021 Rules also remains ambiguous. There are at least 17 petitions filed across various Indian courts (now transferred to the Delhi High Court), challenging the constitutionality of these rules. Given the current legal challenges, it would be prudent for the government to exercise caution in implementing these provisions and instead consider formulating legislation which would protect users from the subsisting and future perils associated with AI whilst in the same breadth protecting and fostering innovation and progress.